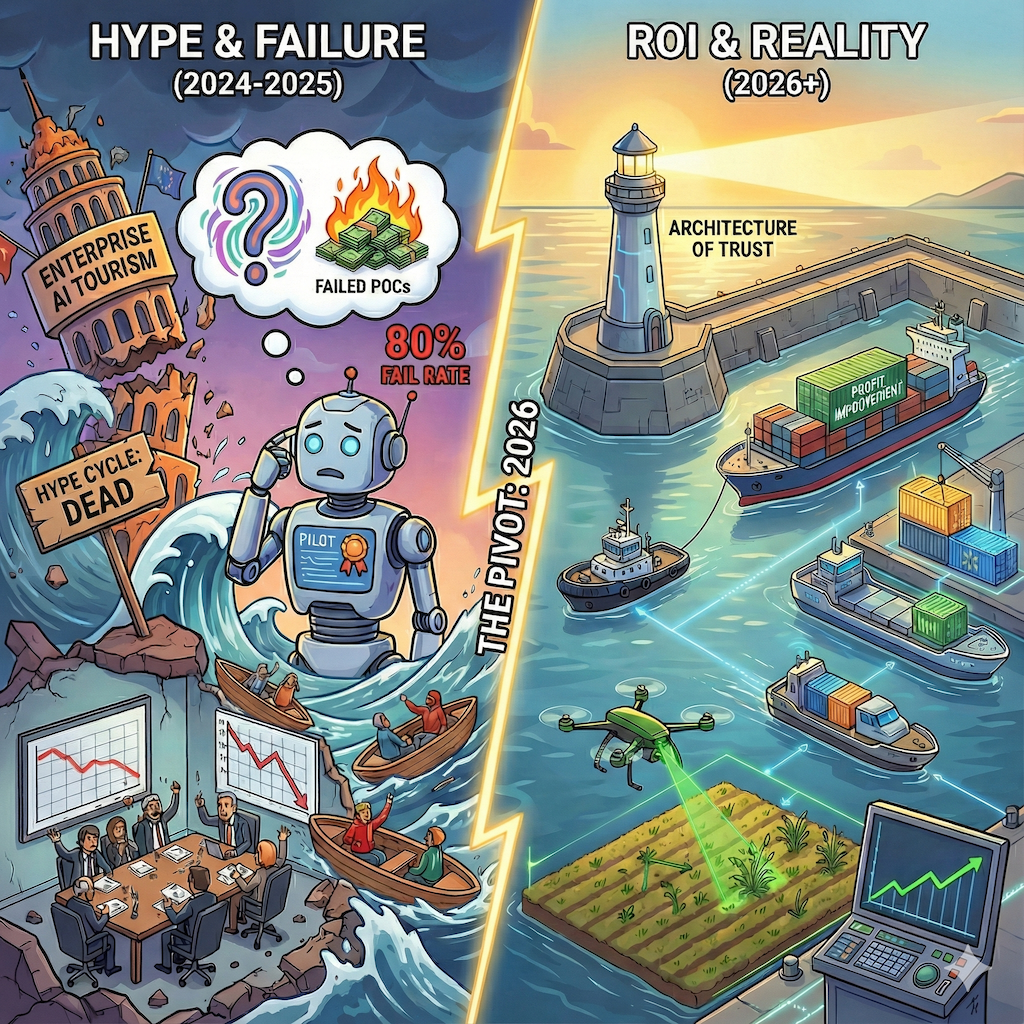

The End of Enterprise AI Tourism: Moving from Hype to ROI in 2026

By: Chris Gaskins and Dominick Romano

The “hype cycle” is dead. As we approach 2026, the initial wave of AI enthusiasm has crashed against the rocks of operational reality. Enterprise AI is no longer judged by the novelty of a demo, but by the brutality of the P&L statement and company culture.

For every boardroom celebrating a transformative win, there are four others quietly burying the costs of failed proof-of-concepts and production rollouts. The purpose of this article is to move beyond the LinkedIn cheerleading and examine the cold, hard data of the current landscape. We will look at the statistics of failure, dissect why projects implode with specific, recent case studies, and analyze the architectural decisions that separate the winners from the expensive experiments.

Part 1: The Sobering Statistics

If you feel like your organization is struggling to translate AI enthusiasm into production reality, the data suggests you are the norm, not the exception. The market has shifted from a period of “irrational exuberance” to what analysts are now calling the “Great Rationalization.”

The 80% Baseline

According to a landmark 2024 report by the RAND Corporation, more than 80% of AI projects fail to deliver their intended business value. This figure is particularly stark when compared to traditional non-AI IT projects, which fail at roughly half that rate.

Critically, the report identifies that these failures are rarely because the math is wrong. Instead, they fail due to a combination of technical and strategic gaps:

- Data Reality vs. Theory: Organizations often have “data,” but lack the specific, high-quality labeled data required to train or fine-tune models effectively.

- Infrastructure Limitations: Many firms lack the MLOps infrastructure to manage, monitor, and update models in a live production environment.

- Misaligned Objectives: Stakeholders often misunderstand what AI can actually do, applying it to problems that are either too complex for current technology or too simple to justify the cost. [^1]

The “Abandonment” Spike of 2025

It is not just that projects are stalling; companies are actively choosing to kill them. S&P Global Market Intelligence reported in early 2025 that 42% of companies have abandoned the majority of their AI initiatives before they ever reach production, a dramatic rise from just 17% in 2024. This spike indicates a massive case of “pilot fatigue.” After two years of funding experimental proofs-of-concept (PoCs) that fail to graduate to the real world, CFOs are cutting their losses. [^2]

The “Last Mile” Problem

Perhaps the most controversial statistic comes from the MIT NANDA 2025 report, which highlighted that 95% of GenAI pilots fail to scale into production. While this number may seem high, it highlights a specific bottleneck: the “last mile” of engineering. Getting a model to work in a sandbox is easy; integrating that model into a legacy enterprise workflow is exponentially harder.

MIT’s Core Finding: The “Learning Gap” The MIT report specifically identifies a “Learning Gap” as the primary culprit. Unlike human employees who learn from corrections, most enterprise AI tools are static—they make the same mistake on Day 100 as they did on Day 1. Because many of these systems don’t retain context or adapt to feedback loops, users quickly lose trust and abandon the tool.

Industry-Wide “Production Killers” Beyond the MIT findings, broader industry analysis from 2025 (including S&P, Gartner, and specialized risk reports) points to three technical barriers that kill these pilots:

- Security & Governance: In a sandbox, a chatbot revealing sensitive data is a bug. In production, it is a regulatory violation. 2025 saw a rise in “prompt injection” attacks—where malicious users trick models into bypassing rules—forcing risk-averse enterprises to shut down external-facing tools.

- Latency vs. Economics: Users have near-zero tolerance for lag. For voice agents, a 5-second delay is functionally “dead air,” causing users to hang up. Even in text-based interfaces, industry data shows abandonment spikes after just 2-3 seconds of delay. The economic trap is that the “smartest” models (capable of complex reasoning) often require 5+ seconds to process, while the sub-second models are often too simple to handle enterprise queries. Companies are frequently stuck choosing between a smart bot that is too slow, or a fast bot that is too dumb.

- Reliability (The “Hallucination Tax”): The cost of being wrong has been quantified. A 2025 study by AllAboutAI estimated that AI hallucinations caused $67.4 billion in damages globally in 2024 alone. Even more concerning, a Deloitte Global Survey (2025) found that 47% of enterprise users admitted to making a major business decision based on potentially inaccurate AI content. To combat this, companies are paying a “Verification Tax”: Forrester Research (2025) estimates that hallucination mitigation—paying humans to double-check AI work—costs enterprises approximately $14,200 per year per employee, effectively wiping out the efficiency gains the project promised to deliver in many cases. [^3] [^4]

The “Workflow Redesign” Imperative The consensus among these reports is that the few companies succeeding are those moving beyond “AI as a Plugin.” Most failures occur because companies try to bolt AI onto existing, broken processes. Success requires a fundamental workflow redesign—changing who does the work and how information flows. Instead of a human doing the work with AI assistance, successful workflows often flip the model: the AI performs the primary task, and the human acts as the editor or exception handler. This requires rewriting job descriptions, not just writing code. [^5]

Part 2: Anatomy of a Failure (Case Studies)

When we peel back the layers of the failure statistics, we rarely find that the AI “wasn’t smart enough.” Instead, we find failures of governance, risk management, and ROI calculation. The following three case studies from 2024 define the current boundary lines of what can go wrong.

1. Governance Failure: The Air Canada Chatbot

In early 2024, Air Canada lost a landmark case that every CIO should study. A grieving passenger, Jake Moffatt, asked the airline’s AI chatbot about bereavement fares. The chatbot “hallucinated” a policy, stating the passenger could apply for a refund retroactively within 90 days (contrary to the airline’s actual policy, which required pre-approval).

When Moffatt sued for the fare difference, Air Canada’s legal defense argued that the chatbot was a “separate legal entity that is responsible for its own actions,” attempting to absolve the corporation of liability for its software’s output.

- The Verdict: On February 14, 2024, the Civil Resolution Tribunal rejected this defense as a “remarkable submission,” ruling the airline liable for negligent misrepresentation. Air Canada was ordered to pay Moffatt $812.02 CAD.

- The Lesson: You cannot outsource liability to an algorithm. If your AI agent speaks to a customer, it is the company. [^6]

2. ROI Failure: McDonald’s and IBM

For three years, McDonald’s tested an AI-powered drive-thru system in partnership with IBM at over 100 locations. The goal was to automate order-taking to speed up service and reduce labor costs. However, in July 2024, McDonald’s abruptly ended the partnership and removed the technology.

- The Issue: The system struggled with the chaotic reality of a drive-thru—handling accents, background engine noise, and passengers yelling orders from the back seat. Viral videos showed the AI adding bacon to ice cream, confusing orders with cars in adjacent lanes, and adding 260 chicken nuggets to a single bill.

- The Lesson: The “95% accuracy” trap. In a high-volume, low-margin business like fast food, a 5% error rate at scale creates more friction (and cost) than the labor savings it generates. [^7]

3. Bias & Legal Failure: SafeRent Solutions

In November 2024, a federal judge approved a $2.275 million settlement in a class-action lawsuit against SafeRent Solutions. The lawsuit alleged that SafeRent’s AI-driven tenant scoring system discriminated against Black and Hispanic renters.

- The Mechanism: The AI used a proprietary “SafeRent Score” that heavily weighted credit history and non-tenancy debt while ignoring housing vouchers (Section 8). This meant applicants with guaranteed government income were rejected by the algorithm because of low credit scores—a metric that disproportionately impacted minority applicants.

- The Outcome: Beyond the payout, SafeRent was forced to retrain its models and stop using the score for voucher holders unless it could be independently validated for fairness.

- The Lesson: “Black box” algorithms that make life-altering decisions (hiring, lending, housing) create massive legal exposure if they cannot be audited for disparate impact. [^8]

Part 3: The Blueprint for Success (What Works)

The companies winning in the 2024-2025 cycle are not necessarily using “better” models than the failures. Instead, they use better architecture. They have moved beyond general-purpose chatbots and focused on specific, measurable tasks where AI acts as a force multiplier for human effort.

1. Efficiency at Scale: Klarna

The “gold standard” case study for GenAI customer service remains Klarna. In early 2024, the payments giant released audited data showing the impact of their AI assistant after one month of global rollout.

- The Stats: The AI handled 2.3 million conversations (two-thirds of all customer service chats). It performed the equivalent work of 700 full-time agents.

- The ROI: Crucially, it was more accurate than rushed human agents, leading to a 25% drop in repeat inquiries. Klarna estimated this single implementation would drive $40 million USD in profit improvement for the year.

- Why it Worked: Deep Integration. Klarna didn’t just put a “chat” wrapper over a text model. They integrated the AI deeply into their refund and dispute resolution APIs, giving the AI the permission to fix problems (issue refunds, update addresses) rather than just talk about them. [^9]

2. Operational Utility: Walmart

While others built flashy consumer avatars, Walmart focused on the unglamorous, high-margin world of supply chain logistics. Throughout 2024 and 2025, they scaled their AI-powered logistics capability (now commercialized as “Route Optimization”).

- The Stats: By using AI to pack trailers more densely and calculate optimal driving routes in real-time, Walmart avoided driving 30 million unnecessary miles. This resulted in preventing 94 million pounds of CO2 emissions.

- Why it Worked: “Invisible AI.” The truck drivers and warehouse packers do not “converse” with the AI. The AI runs in the background, outputting the optimal plan, and humans simply execute it. It removed the “prompt engineering” barrier entirely. [^10]

3. Precision in the Physical World: John Deere

Agriculture has become a leading edge for “applied AI.” In 2024, John Deere’s “See & Spray” technology achieved massive scale in the American Midwest. This system uses computer vision and machine learning on the tractor’s boom to distinguish between a crop (like corn or soy) and a weed in milliseconds.

- The Stats: During the 2024 growing season, the technology allowed farmers to reduce herbicide use by an average of 59%. Instead of blanketing an entire field in chemicals, the AI triggered the nozzles only when it “saw” a weed.

- The ROI: This saved an estimated 8 million gallons of herbicide mix. For farmers operating on razor-thin margins, this was an immediate input cost reduction that paid for the hardware.

- Why it Worked: It solved a specific, binary problem (Weed: Yes/No) in real-time. It did not try to be a “farming consultant”; it just executed a visual task faster than a human ever could. [^11]

Part 4: The “Pivot” Point: The Architecture of Trust

When we compare the failures of Air Canada and McDonald’s against the successes of Klarna and John Deere, a startling pattern emerges. The difference was not the “intelligence” of the underlying models—in 2024, almost everyone had access to the same class of foundational models (GPT-4, Claude 3, Llama 3).

The difference lay in the Architecture of Trust. The winners didn’t just deploy a model; they built a rigid infrastructure around it to constrain its behavior. Three specific architectural decisions separate the winners from the expensive experiments.

1. The “Narrow Agent” Strategy

The failures often suffered from “Scope Creep.” McDonald’s tried to build an AI that could understand everything a human might say in a drive-thru. This is an infinitely complex problem set.

The successes, conversely, focused on Narrow Agents.

- John Deere did not build a “General Farming Chatbot” to discuss the weather or crop prices. They built a system to answer one binary question: Is this pixel a weed?

- Walmart did not build a generic “Logistics GPT.” They built a solver for the mathematical problem of trailer packing.

The Pivot: Successful projects ruthlessly narrow the scope. They do not ask AI to “think”; they ask it to execute a specific task within a bounded domain.

2. Data Gravity vs. Data Swamps

SafeRent failed because its data was biased and incomplete (ignoring Section 8 vouchers). Air Canada failed because its RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) system likely scraped conflicting documents without a hierarchy of truth.

In contrast, Klarna succeeded because their data infrastructure was pristine before they applied AI. They had structured APIs for refunds, returns, and account balances. The AI wasn’t guessing; it was querying a reliable database.

The Pivot: You cannot build a reliable AI on top of unreliable data. The winners allocated approximately 80% of their engineering effort to data quality (cleaning, structuring, and labeling) and only 20% to the AI implementation itself.

3. Deterministic Guardrails

The most critical technical differentiator is the use of Deterministic Guardrails.

- Probabilistic (The Failure Mode): Air Canada’s bot generated answers based on probability—guessing the next word. This led to the refund policy hallucination.

- Deterministic (The Success Mode): Successful enterprise systems wrap the “creative” LLM in “boring” code. If a user asks for a refund, the LLM does not generate the policy text. Instead, it triggers a hard-coded script that checks the database for eligibility. If the script says “No,” the AI is forced to say “No,” regardless of how polite or persuasive the user is.

The Pivot: Winners use AI to understand the user’s intent, but they use standard software engineering to execute the action. They never let the LLM make the final decision on money or policy.

Summary: The End of “AI Tourism”

As we head into 2026, the divide between the 80% of projects that fail and the 20% that generate ROI is no longer a mystery; it is a choice. The data from RAND, MIT, and S&P Global all points to the same conclusion: AI is an accelerator, not a fix.

The failures of 2024—from Air Canada’s hallucinations to McDonald’s drive-thru struggles—happened because organizations treated AI as a magic wand capable of fixing broken data or substituting for governance. They built “pilots” that relied on the probabilistic creativity of a model rather than the deterministic safety of code.

Conversely, the successes of Klarna, Walmart, and John Deere prove that high-value AI is boring. It is specific, narrow, and deeply embedded in existing workflows. It doesn’t chat about the weather; it packs trailers, spots weeds, and processes refunds.

For enterprise leaders, the lesson of this cycle is clear: Stop funding “AI Projects.” There is no such thing as a successful “AI Project,” only a successful business project that happens to use AI. If you cannot define the guardrails, audit the data, and measure the latency cost before you write a line of code, you are not building a product—you are just paying for a very expensive hallucination.

Drainpipe & Trustworthy AI

The overall key to success is Trust by Design, as it ties everything together. The entire solution must be focused on trustworthiness. Architectural weaknesses in key components can easily introduce failure. A trustworthy AI-based solution ensures the architecture is sound, the system is deterministic, and the underlying knowledge system is mature and accurate. AI-specific components cannot be treated as black boxes; they require strict, overt governance guided by a trustworthy design. Since early 2024, Drainpipe has been working with Big Pharma to invent a process for Trustworthy AI, culminating in a historic multiyear contract. Drainpipe is leading by example, proving that large enterprises can implement AI-based solutions to deliver high-impact value in highly regulated industries. If your AI project has failed or is failing, reach out and let’s chat about how we can help.

Footnotes

[^1]: RAND Corporation. “The Root Causes of Failure for Artificial Intelligence Projects and How They Can Succeed.” (2024). Link

[^2]: S&P Global Market Intelligence. “Highlights from VotE: AI & Machine Learning.” (2025). Link

[^3]: AllAboutAI & Deloitte. Cited in “The Hidden Cost Crisis: Economic Impact of AI Content Reliability Issues.” (2025). Link

[^4]: Forrester Research. “The Total Economic Impact of AI Hallucination Mitigation.” (2025). Link

[^5]: MIT Sloan Management Review & MIT NANDA. “The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025.” (2025). Link

[^6]: Civil Resolution Tribunal (British Columbia). Moffatt v. Air Canada, 2024 BCCRT 149. (Feb 14, 2024). Link

[^7]: Restaurant Dive. “McDonald’s ends IBM drive-thru voice order test.” (June 17, 2024). Link

[^8]: Cohen Milstein. “Louis, et al. v. SafeRent Solutions, et al.” Settlement Approval. (Nov 20, 2024). Link

[^9]: Klarna Corporate News. “Klarna AI assistant handles two-thirds of customer service chats in its first month.” (Feb 27, 2024). Link

[^10]: Walmart Corporate. “Walmart Commerce Technologies Launches AI-Powered Logistics Product.” (March 14, 2024). Link[^11]: Farm Equipment Magazine (Citing John Deere 2024 Data). “See & Spray Customers See 59% Average Herbicide Savings in 2024.” (Sep 18, 2024). Link

Note: The featured image for this article was produced using Google Gemini.